Pokemon Go just went live and what a start! US$1.6 million spent in the US in the first day, only 14 hours to become #1 in the App Store and it has already been installed more times than Tinder. The immediate success of Pokemon Go has increased Nintendo’s stock price by 50%, however, the long-term revenues are being challenged by analysts and people now point out that Apple takes 30% cut from in-app purchases (or US$480’000 of the US sales) and that Google invested in Niantic, the company behind the game using Nintendo’s franchise.

This is just the beginning as the sequenced global roll out has been slowed down by servers crashing, leaving people in Hong Kong imagining where they would be able to catch them all. Beyond this headline news that we all know, there is a chance to look at Pokemon Go from a fresh perspective. Indeed, the game (or the hype behind it) creates opportunities and challenges found at the nexus of Finance, Insurance, Privacy and Regulation. This article will therefore look at the following:

- Finance: How Augmented Reality Turns a Virtual Game into Real Cash?

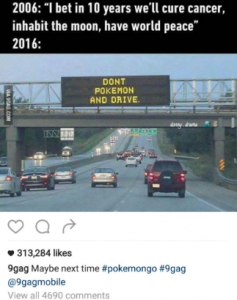

- Insurance: Why you shouldn’t #PokemonGo and Drive?

- Privacy: When Telling me where you are Tells me who you can Catch?

- Regulation: How a Child’s Game Broke its Sandbox?

Pokemon 101: Old Brand, Same Principle & New Format

First things first, Pokemon was co-created in 1995 by Ken Sugimori and & Satoshi Tajiri (not to be mistaken by Satoshi Nakamoto the alleged, but contested, creator of Bitcoin). I still remember how when I was eight years old I would trade cards in school or pull out my Gameboy for a bit of 1-Vs-1 (hint: my favorite Pokemon was Blastoise).

As a result, there is a strong and strange nostalgia pushing me to play Pokemon Go. Pokemon is a brand that I know and even if I never followed the subsequent evolution of the franchise (1998 – 2016), I want to get on board a (re)play the game. I started to read and watch a few dozen videos (this is the best YouTube gaming channel for Pokemon Go, with approx. 2million daily views). This link between myself and the franchise is priming a behavior that would make me more likely to download and use, but perhaps not to the stage that I trust more this tech brand as a bank to manage my money.

Finance: How Augmented Reality Turns a Virtual Game into Real Cash?

Whilst I won’t give a step-by-step guide on how to play Pokemon Go, there are two features to know in order to understand how businesses are driving footfall and increasing (real) cash revenues. First “PokeStops” are pre-determined locations where “trainers” can get free items. However, since the game is location-based, trainers need to be within a close radius of the Pokestop to get the items. The opportunity, or problem, is that certain locations become suddenly popular as players converge towards them for free goods. For example, the church of England has now applied to become an official “Pokestop” but so was the house of an ex-sex offender.

Since Pokestops are pre-determined (for now, eventually people can apply here), shop owners can bring people in by purchasing “lures”, which will attract Pokemon near the area for a limited time, in turn attracting players and therefore potential consumers. Like most freemium games, lures are paid add-ons to be purchased with “PokeCoins” using real cash. Buying 14’500 PokeCoins will cost you a real US$100, since lures only work for 1h, it will cost a business US$1.19/hour to attract potential consumers to their shop whilst they play their virtual game.

Banks have understood the value of increasing footfall, in the ever diminishing branch network. Avidia Bank, in the US, has spotted the opportunity and already started to communicate on social media about it.

However, the application of augmented reality within banking apps is not new. In 2010, Common Wealth Bank in Australia introduced an app where by simply pointing the phone’s camera to the house you wish to buy, it would overlay pricing information and the terms of mortgage. This video here shows a demo, but also gives interesting stats: 117,246 downloads in 24 weeks, 1.2 million properties searched and 109% return on marketing costs. Of course, comparatively to Pokemon Go, the above is negligible. However, the long-term impact is that Augmented Reality is gradually becoming part of people’s daily habits. Indeed, Pokemon Go is used 33 min/day per user (ss 22m for Facebook and 18m for SnapChat). In other words, banks should think of the following sentence: “teach me how to use Pokemon Go and I will show you how to buy your next house via your phone.”

Insurance: #Don’t PokemonGo and Drive

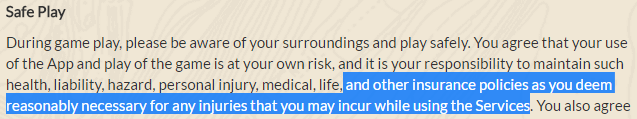

By getting millions out in the streets (watch mayhem in New York as rare Pokémon got spotted) Pokémon Go has already made headlines. People found dead bodies,trespassing is increasing, phone theft reported and even two men fell off a cliff. Irrespective of whether the reported stories are true or hoaxes, what is interesting is looking at the T&Cs of the app:

Most likely, you are one of the 93% of people not reading T&Cs and the insurance industry has got you covered. The above picture makes clear that it is your responsibility to have the adequate policies. Waiving liability this way by simply transferring it on the consumers feels reasonable, however, it won’t always work.

If in doubt, once you (or your kid…) installs the app, make sure that you have the right: Home Insurance (e.g. for theft), Motor Insurance (e.g. If you hit a (real) Pokémon Trainer, Identity Theft protection (e.g. start credit scoring on the back of your Pokedex). Perhaps Nintendo should go in the InsurTech world and sell an “all-in-one PokeCare Plan” as they have the data to check where, when and who is going in unauthorized places. This might not be an ill-advised move, especially since the InsurTech industry grew 237%, reaching US$2.6 billion in 2015.

Privacy: Tell me where you are and I will tell you who you can catch

On top of the augmented reality of Pokémon Go, the app uses your location (and time) to adapt the types of Pokémon you can catch. For example, being near a lake will enhance your chances of getting a water type Pokémon. However, like every technology, not everything is perfect and some GPS accuracy creates some graphic scenes:

More seriously, the app raises important data privacy questions as well as an illustration of how, if done right, consumers are willing to enter into a value exchange between their data and a firm’s products or services. The app requires a constant GPS signal to work, meaning that at any given time it will know where you are. Questions about how long and why that data is stored are emerging.

Most recently, Google opened up all the data it holds on us, by making My Activity Page available. Within minutes you see all the location data that google has, your watched YouTube history, but also the recordings of your voice and audio activity if you use the voice control function. If unsettling, (visualizing that Google knows you more than yourself, tracing back details that are over 5 years old…), Google’s push is welcomed as it enhances the concept around data sovereignty, which is favored by the EU General Data Protection Regulation and Blockchain use cases.

Yet, the bottom line is that we users, are having our information (data) and our context (meta-data) consistently mined by apps and companies. While not suggesting that we should go against this trend where Data is the New Oil, the need for a better understanding of the (un)intended consequences of consumers’ data aggregation is clear.

Regulation: The child’s game that broke the sandbox?

The meteoric rise of Pokémon Go has also demonstrated the limits of controlling growth in an era of social media buzz and virality. In less than a week Pokémon Go had over 9.5 million users. Technological availability, like the mobile phone, which marks consumers’ entry into the 4th industrial revolution, has radically changed the speed of penetration for new products and start-up growth. Indeed, it took 35 days for Angry Bird to do what the telephone did in 75 years.

It is fair to say that Pokémon Go is at this stage still an experiment, with a lot of features yet to be released. Recent reports that it is misusing consumers’ data (e.g. location, gmail integration, etc.) to test a new business model raises questions about one of the purposes of a regulatory sandbox, namely the access to “raw consumer data”. Certainly, the submission process to join the sandbox, covers an in-depth due-diligence procedure on what and how data will be used in order to understand the competitive add-value and maintain consumer protection.

However, what is not clear to me is to what extent the “exit” from the sandbox has been considered by regulators. Pokémon Go has gone from “to-small-to-care” to “too-big-to-fail” quite literally overnight. In practice, this challenges the capacity of regulators to exactly pinpoint when a firm creates sufficient market risk to justify its supervision/regulation, and even removal of the sandbox. Furthermore, should market risk be defined by number of consumers (e.g. 10m in 1 week), bugs on the products (e.g. app freeze) or external hacks (e.g. DDOS attack)? In practice, I therefore question if regulators ever considered how to make a start-up “safe-to-fail” within its sandbox environment, especially as we all know that over 90% of start-ups do fail. Certainly, this is an open question as regulatory sandboxes are themselves being piloted in four countries to date and we can expect future updates as these go live.

Alright, enough reading and now go out and catch ‘em all! But also let’s remember that sometimes there are other more important problems to analyses and fix. Indeed, it was mentioned that Silicon Valley should stop solving for: What is my mother no longer doing for me?, but instead how they can have a bigger impact in the world.